Why We're So Cruel to People in Prison

Imagine you’re a cave person 10,000 years ago.

Each day when you go out to gather food, your brain is on high alert because you could die any number of ways. This sense of alertness comes from the limbic part of your brain just above your brain stem. When you’re afraid, the amygdala, specifically, has full control of your mind and body. The amygdala is what signals your body to fight or flee when danger arises.

Out of the corner of your eye you see a figure move. In a split second you drop the berries you picked and raise your club to fight. The brain has released cortisol into the bloodstream so your metabolism is increased. Increased metabolism makes your heart beat fast. Blood is especially routed to the hands and feet so you can do whatever is necessary to survive.

The figure moves again and now you can make out what it is. It’s another cave person, out gathering berries. As this new figure moves into the light, you get a good look.

Your senses immediately take them in: size, clothing, skin tone, age, hair color, smell, etc. This sensory information is sent to your prefrontal lobe just behind your forehead where empathy, logic, and analytical thinking live. The prefrontal lobe analyzes the sensory input, and that’s where things get technical.

In your prefrontal lobe there are two “tunnels” right smack in the middle. These tunnels are called the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC).

(Note: they’re not actually tunnels, but it’s a helpful way to understand them).

In a fraction of a second, your prefrontal lobe makes a judgment: it classifies the figure as “familiar” or “unfamiliar” and sends a signal into one of the tunnels.

If the figure is familiar - if it’s just Gronk from the cave next door - the signal goes to the vmPFC which routes itself right back into the prefrontal cortex so empathy and logic can take over. In this case, no defenses are necessary. No need to fight or run. No need to put up real or invisible separation. The brain and body can be vulnerable because the person is familiar, and is therefore safe.

But, if the figure is unfamiliar, a signal goes to the dmPFC which has a strong connection with the amygdala and limbic area. The alert that originally went through the body intensifies. Defenses are activated. Metabolism increases. Blood stays in the hands and feet. Your brain tells your body that it’s under duress. The person is unfamiliar and therefore unsafe. The brain does everything it can to help the body survive at all cost.

Here’s the important part: when we believe we are under duress because of the presence of an unfamiliar person, our prefrontal cortex - where empathy lives - is deactivated. It is neurologically impossible to access empathy for another person when our brains tell us to fear them. When there is no empathy, there is no limit to the harm we will justify inflicting on a person who makes us feel unsafe because our brains prioritize our own safety and survival above all else.

If harm befalls the unfamiliar person, so be it. It just increases our odds of survival.

Actually, it goes even further than that.

UNFAMILIAR PEOPLE ARE LESS HUMAN

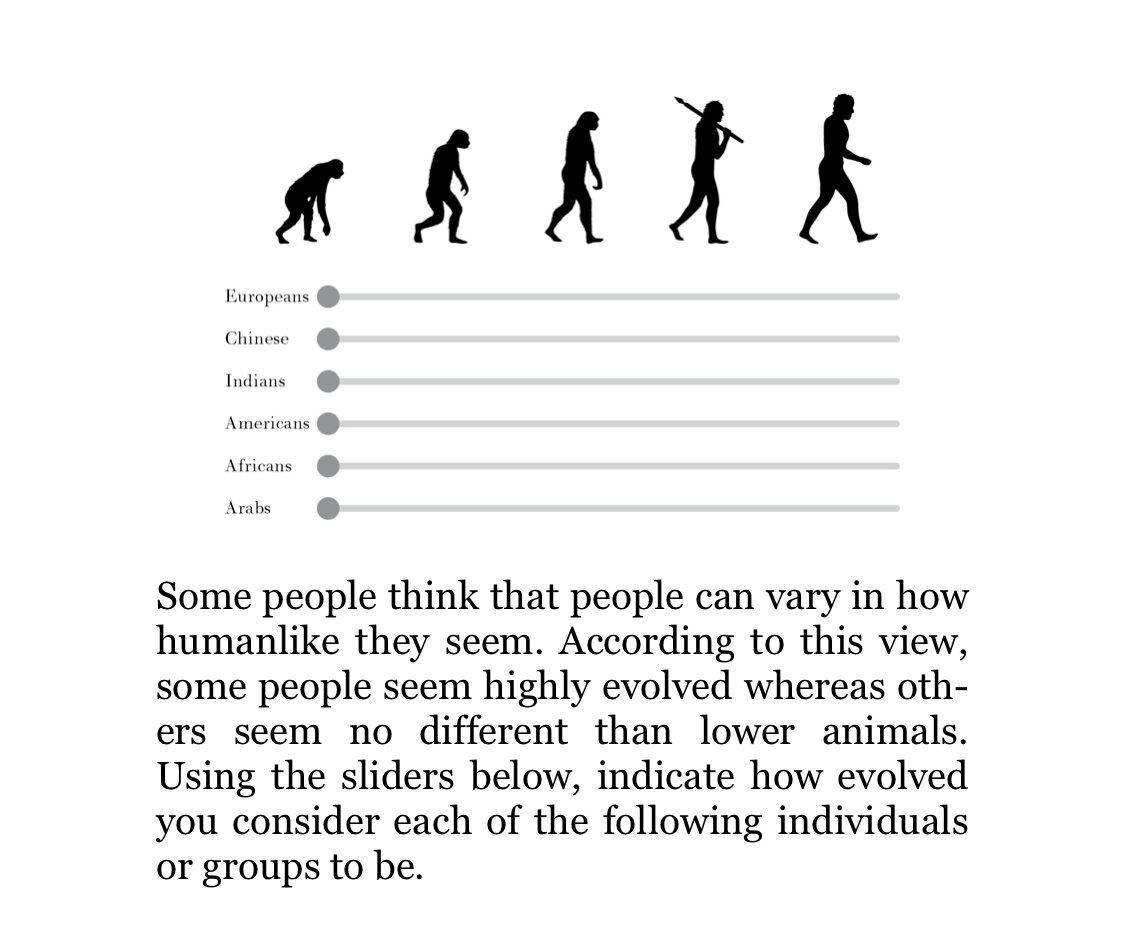

In his book The War for Kindness, Jamil Zaki references a 2015 study by psychologist Nour Kteily. He and his colleagues showed people this scale:

Participants used the sliding bars to rate how human various groups of people are. In one study in America where participants were mostly white, Arabs were rated on average 75% human. Mexican immigrants were rated 80%. As you might expect, support for anti-Muslim immigration policies and interrogation tactics like waterboarding were much higher among those who saw Muslims as less human.

Zaki also writes:

“A century ago psychiatrists shackled psychotic patients in ice water baths for hours on end, claiming they couldn’t feel cold. One physician working in the nineteenth century remarked, ‘What would be the cause of insupportable pain for White men, a Negro would almost disregard.’ Even now, people guess that a black person will feel less pain from a syringe or burn than a white person.”

When fear controls our minds, we prioritize our own survival above all else. But fear also causes us to see unfamiliar people as less human. And so we justify any and every atrocity against them.

Which brings us to prisons.

PEOPLE IN PRISON ARE HUMAN

This week, two articles were released about the Cummings prison unit here in Arkansas. They tell a gruesome story of how people living in prison were an afterthought when it came to enacting social distancing and quarantine standards throughout the state.

At least 11 people living in the Cummings unit have died from COVID-19, making it one of the largest Coronavirus “hot spots” in Arkansas, if not the southeast.

Sure, it's easy for folks like us in the free world to read these reports and think, "Well that's part of being in prison. If you can't do the time, don't do the crime."

It's easier still when people in prison are kept out of sight and out of mind. When they're bussed out to remote areas, locked behind walls and thrown in cages, our brains naturally classify them as unfamiliar, unsafe, not human. Fear deactivates empathy.

The solution for protecting people in prison from COVID-19 is not simple. But it cannot start from a place of fear. It must begin with empathy, with the fundamental fact that every person is a human being with worth and value. Because empathy reveals humanity.

Compassion Works for All teaches that a consistent mindfulness and meditation practice increases empathy by reducing the mind's reliance on the fear center of the brain. Connections to the amygdala and limbic area deteriorate the more we engage in mindful focus and activity.

The Coronavirus pandemic can open our eyes to our shared humanity. Just as you might take precautions to avoid the virus, people in prison would like to do so too. Just as you want to protect your children, spouse, parents, grandparents, friends, and family members, every person in prison is someone's child or spouse or parent or grandparent or friend or family member. Someone somewhere is worrying about whether their loved one is being exposed to the virus while living in prison.

Surely we can all understand what that feels like.

If collectively we removed fear and practiced empathy toward people in prison, we might remember that exposure to a deadly virus is not part of anyone’s “time.” Neither is sexual assault, slave-like labor, mental and emotional trauma, financial exploitation, or disproportionate levels of punishment based on race and sexual identity.

If we can understand that, then maybe we can also see that our entire prison system is broken. Arkansas has one of the highest recidivism rates in the country, which tells us that our current punishment system doesn't work. If prison is supposed to be a deterrent to crime, few people are being deterred.

The answer, therefore, is not more brutality; it's more humanity.

More drug treatment.

More mental health centers.

More after-school programs and community development foundations.

More access to basic health services.

More financial literacy and education.

More social workers than police officers.

More affordable housing.

More job training and employment.

More continuing education.

These are the things human beings need to thrive. If we see people who commit crimes as humans with human needs, we cannot help but change how we treat them.

Cruelty has proven itself unsuccessful. Perhaps it's time to let go of fear, and give empathy a shot.